Inside the US$15 billion bet that will either transform Zimbabwe or finish what Zanu PF’s collapsed businesses started

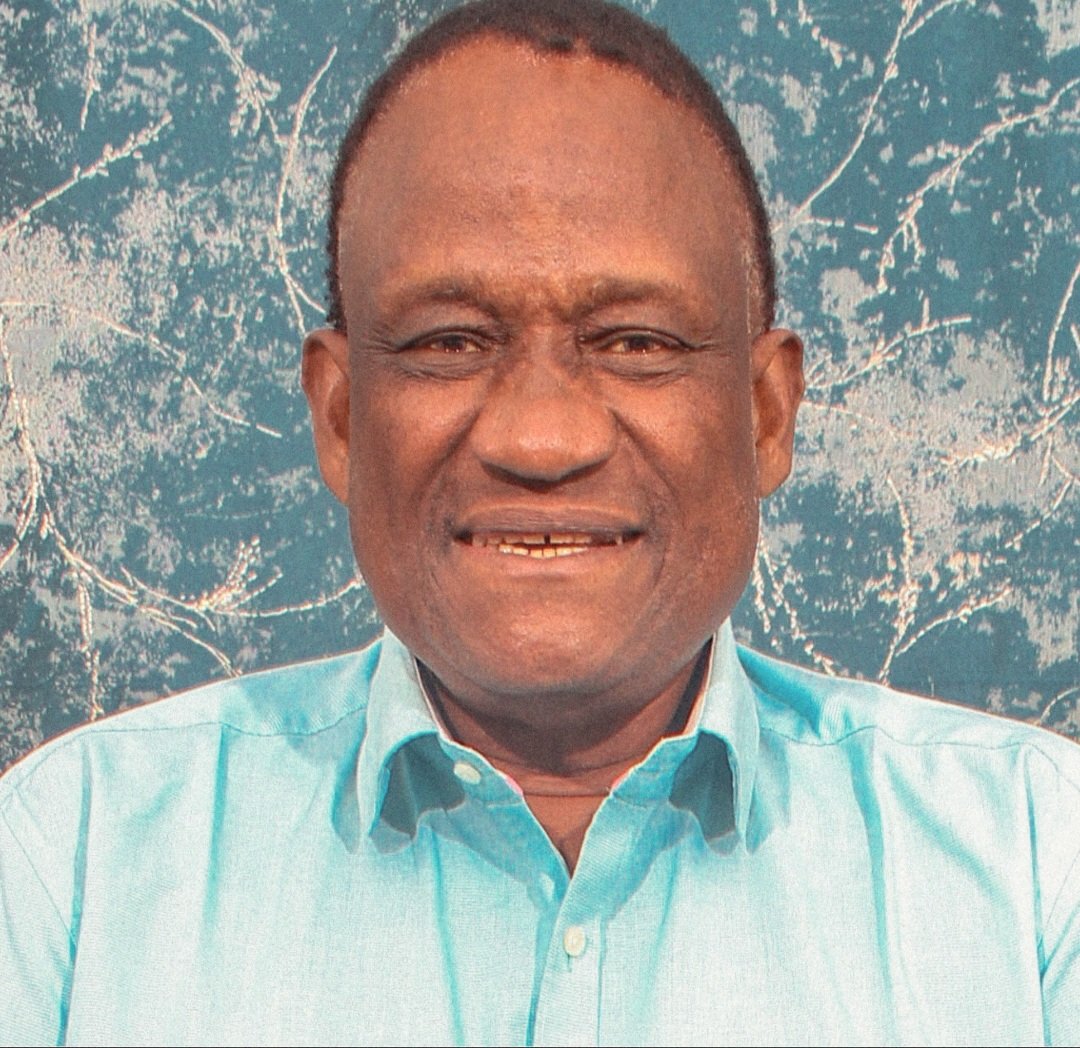

THE photograph surfaced in January 2026: John Panonetsa Mangudya, former Governor of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, standing at a podium in his new capacity as Chief Executive Officer of the Mutapa Investment Fund. He spoke of “accountability to the Zimbabwean people” and “world-class governance standards.”

The audience applauded.

Nobody mentioned that Mangudya had promised to resign if his bond notes failed. They failed. The currency collapsed from 1:1 to 25,000:1 against the United States dollar. He did not resign. He was promoted.

This is the man now entrusted with US$15 billion in public assets — Zimbabwe’s largest single concentration of wealth. This is the fund named after an empire that collapsed under the weight of foreign interference, succession wars, and corrosive infiltration of external interests into internal governance.

The ironies would be poetic if the stakes were not existential.

I. What Problem Are We Solving?

Before examining whether the Mutapa Investment Fund will succeed or fail, a question proponents have deliberately obscured demands an answer: what problem is this fund designed to solve?

The official narrative is straightforward. Zimbabwe’s state-owned enterprises have hemorrhaged money for decades. They require professional management, recapitalisation, and insulation from political interference. A sovereign wealth fund, modeled on Singapore’s Temasek or Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global, will transform loss-making liabilities into wealth-generating assets.

This narrative is not wrong. It is incomplete.

The deeper question is this: who created the problem we are now attempting to solve?

Zanu PF has governed Zimbabwe without interruption since 1980. The state-owned enterprises now transferred to Mutapa were managed by Zanu PF appointees for forty-four years. The corruption that gutted these entities occurred under Zanu PF supervision. The political interference that prevented commercial discipline came from Zanu PF cadres.

The uncomfortable reality polite analysis avoids is that the people who created the problem are now designing its solution. The party that looted state enterprises now controls the fund into which those enterprises have been placed. The President who signed the statutory instrument creating Mutapa also signed the orders exempting it from parliamentary oversight and procurement law.

On what basis should Zimbabweans believe the same political formation will behave differently simply because assets have been reorganised under a new holding structure?

This is not cynicism. It is pattern recognition.

II. The Zanu PF Business Graveyard

To understand what Mutapa might become, one must examine what Zanu PF businesses have already become.

ZIDCO Holdings and M&S Syndicate: The First Experiment

In the early 1980s, riding the optimism of independence, Zanu PF established two holding companies—ZIDCO Holdings and M&S Syndicate—to manage party investments. The Joshi family, Jayan and Manoo, Malawian Asian businessmen who had supported the liberation struggle from Britain, were entrusted with management.

The companies proliferated. At various points, Zanu PF controlled interests in FBC Bank, Treger Holdings, Catercraft, Zidlee Enterprises, Ottawa Property Management, Jongwe Printers, National Blankets, Woolworths, SMM Holdings, Lobels Bread, Fibrolite, and multiple farms including Jongwe and Nyadzonya.

Rambhai Patel, a Kenyan Asian businessman, provided 45 percent of ZIDCO’s equity capital through his London-based Unicorn Export-Import. In 1984, he cemented the relationship with a US$50,000 donation to Zanu PF.

Emmerson Mnangagwa, then Secretary for Finance and later Secretary for Administration, was credited with helping build ZIDCO. He served as chairman of M&S Syndicate until 1990 and wielded influence over both holding companies throughout their operation.

The 2005 Politburo Investigation

In July 2005, Zanu PF’s Politburo debated a devastating internal document: The Report of the Committee on Party Investments.

The committee—comprising David Karimanzira, the late General Solomon Mujuru, Obert Mpofu, Simba Makoni, and Thokozile Mathuthu—found that companies supervised by Mnangagwa were “in shambles due to gross mismanagement and corruption.”

M&S Syndicate investments had collapsed or were hemorrhaging money. Catercraft had not been audited for four years. Board meetings had not been held for two years. National Blankets was dormant. Zidlee’s attempt to acquire Delta failed.

The Joshi brothers fled to Britain as the probe began. Assets were frozen. Police sources later revealed Mnangagwa was being investigated on thirty-nine fraud counts. General Mujuru died in a mysterious fire before presenting the final report. The investigation ended. No charges were filed.

The US Treasury Assessment

In January 2008, the US Treasury added ZIDCO Holdings and Jongwe Printing to its sanctions list, citing their role in aiding the Mugabe regime’s economic destruction. This was not propaganda. It was forensic financial assessment.

The lesson was clear: Zanu PF’s political culture—patronage over performance, party interests over public good—corrupts every institution it touches.

Mutapa exists within this same culture.

III. The Sakunda Precedent

If ZIDCO was the first generation of party capture, Sakunda represents its mature form.

In September 2025, Vice President Constantino Chiwenga alleged Zanu PF owned 45 percent of Sakunda Holdings through a trust structure. He demanded Kudakwashe Tagwirei return the stake and that looted funds be repaid to Treasury.

Chiwenga alleged US$3.2 billion had been siphoned through Sakunda since 2012, largely via Command Agriculture—a programme subsidised by public debt, guaranteed by Treasury Bills, and never transparently audited.

Both the United States and the United Kingdom sanctioned Tagwirei and Sakunda for corruption and misappropriation of public funds.

IV. The US$1.6 Billion Kuvimba Transaction

Between late 2023 and mid-2024, Mutapa acquired a 35 percent stake in Kuvimba Mining House for approximately US$1.6 billion in Treasury Bills.

A 2022 government valuation placed Kuvimba’s total value at US$1.5 billion. Thirty-five percent should have cost roughly US$525 million. Instead, Mutapa paid US$1.6 billion, implying a company valuation of US$4.57 billion—an 85 percent annual appreciation during economic contraction.

The beneficiaries of this payment remain undisclosed.

Investigations previously revealed Tagwirei secretly controlled up to 35 percent of Kuvimba through shell structures. Authorities refuse to identify who received the Treasury Bills.

This pattern—opaque ownership, inflated valuations, public debt payments, and “commercial confidentiality”—has a name elsewhere: state capture.

V. The Mangudya Question

Mangudya promised to resign if bond notes failed. They failed catastrophically. He did not resign.

He now oversees US$15 billion in national assets.

Global Finance consistently rated him D-grade. His successor stated bluntly that bond notes “were never backed by anything.”

This is not the profile of an independent technocrat. It is the profile of a compliant political operator.

VI. Why Singapore and Norway Worked—and Zimbabwe Has Not

Norway’s sovereign wealth fund operates under strict parliamentary oversight, radical transparency, independent auditing, and legal separation of political authority from fund management.

Mutapa has none of these safeguards.

Singapore’s Temasek succeeded because it operates in a meritocratic, low-corruption system. Zimbabwe’s system is designed to suppress independent judgment.

You cannot copy outcomes without copying inputs.

VII. The 1MDB Warning

Malaysia’s 1MDB collapsed because of exemptions, political control, and opacity—the same structural features now embedded in Mutapa.

The theft took years to surface. By then, US$4.5 billion was gone.

Mutapa is following the same blueprint.

Conclusion

The Mutapa Investment Fund will either transform Zimbabwe or finish what Zanu PF’s collapsed enterprises started. There is no neutral outcome.

Its architecture already reveals its purpose.

The refusal to disclose beneficiaries, restore oversight, or submit to scrutiny is itself the most damning evidence.

If Mutapa truly serves the national interest, transparency would cost nothing.

The continued resistance to disclosure answers the question of whose interests it really serves.